There’s no doubt that Americans love coffee. Even last spring, when the pandemic shut down New York, nearly every neighborhood shop selling takeout coffee managed to stay open, and I was impressed by how many people ventured out to start their stay-at-home days with their favorite store-made brew.

An elderly friend who, before the pandemic, would take the subway from Brooklyn to Manhattan to buy her favorite blend of ground coffee, was able to have it delivered to her home. “It was worth the extra cost,” she told me. I use machine-brewed coffee pods, and last summer, when it seemed reasonably safe to go shopping, I stocked up on a year’s supply of the blends I like (luckily, the pods are now recyclable).

We should all be glad to know that whatever we’ve had to do to secure that favorite cup of coffee, may have helped us stay healthy. Certainly, the latest studies on the health effects of coffee and its main active ingredient, caffeine, are reassuring. Its consumption has been linked to a reduced risk of all kinds of ailments, including Parkinson’s disease, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, gallstones, depression, suicide, cirrhosis, liver cancer, melanoma, and prostate cancer.

In fact, in numerous studies around the world, daily consumption of four to five 8-ounce cups of coffee (about 400 milligrams of caffeine) has been associated with reduced mortality rates. In one study of more than 200,000 participants followed for 30 years, people who drank three to five cups of coffee a day, with or without caffeine, were 15 percent less likely to die from all causes than people who avoided coffee. Perhaps most dramatic was a 50 percent reduction in suicide risk among men and women who were moderate coffee drinkers, perhaps because it stimulated the production of brain chemicals that have antidepressant effects.

As a report published last month by a research team at Harvard University’s School of Public Health concluded, although current evidence may not justify recommending that coffee or caffeine be consumed to prevent disease, for most people drinking coffee in moderation “can be part of a healthy lifestyle.”

It wasn’t always this way. I’ve lived through decades of sporadic warnings about the potential health harms of coffee. Over the years, coffee has been blamed for ailments such as heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, pancreatic cancer, anxiety disorders, nutrient deficiencies, acid reflux disease, migraines, insomnia, and premature death. As recently as 1991, the World Health Organization had coffee on its list of possible carcinogens. In some of the now-discredited studies, smoking, and not drinking coffee (the two often went hand in hand), were blamed for the alleged harm.

“These periodic fears have produced a very distorted view in the public,” said Walter C. Willett, a professor of nutrition and epidemiology at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Overall, despite various concerns that have come out of the blue over the years, coffee is incredibly safe and may have several important benefits.”

That’s not to say that coffee is the best certificate of good health. Caffeine crosses the placenta and reaches the fetus, and drinking coffee during pregnancy can increase the risk of miscarriage, low birth weight, and premature birth. Pregnancy alters the way the body metabolizes caffeine, and women who are pregnant or breastfeeding are advised to abstain entirely, drink only decaffeinated coffee or at least limit their caffeine intake to less than 200 milligrams a day — the amount in about two standard-sized cups of coffee in the United States.

The most common negative effect associated with caffeinated coffee is sleep disruption. In the brain, caffeine binds to the same receptor as the neurotransmitter adenosine, a natural sedative. Willett, one of the authors of the Harvard report, told me: “I really like coffee, but I only drink it occasionally because otherwise I don’t sleep very well. A lot of people with sleep problems don’t recognize the connection with coffee.”

Last winter, when Michael Pollan discussed his audiobook about caffeine with Terry Gross on NPR, he said that caffeine was “the enemy of good sleep” because it interferes with deep sleep. He confessed that, after the challenging task of giving up coffee, “I went back to sleeping like a teenager.”

Willett, 75, said, “You don’t have to completely cut out consumption to minimize the impact on sleep.” But he acknowledged that a person’s sensitivity to caffeine “is likely to increase with age.” People also metabolize coffee at highly variable rates, so some may sleep soundly after drinking a caffeinated coffee for dinner, while others have trouble falling asleep if they drink coffee for lunch. Still, whether you can fall asleep without a hitch after an afternoon of coffee may affect your ability to get adequate deep sleep, Pollan says in his upcoming book, “This Is Your Mind on Plants.”

Willett said it’s possible to develop a tolerance to caffeine’s effect on sleep. My 75-year-old brother, a regular caffeinated coffee drinker, says it does not affect him. But building up a tolerance to caffeine could mitigate its benefits if, say, you want it to help you stay alert and focused while driving or taking a test.

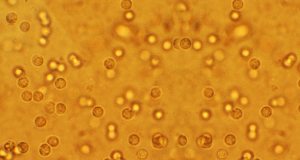

Caffeine is one of more than a thousand chemicals in coffee, not all of which are beneficial. Among those that also have positive effects are polyphenols and antioxidants. Polyphenols may inhibit cancer cell growth and reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes; antioxidants, which have anti-inflammatory effects, may counteract heart disease and cancer, the country’s leading killers.

None of this is to imply that coffee is beneficial no matter how it is prepared. When it is brewed without a paper filter, such as in a French press, Norwegian boiled coffee, espresso, or Turkish coffee, oily chemicals called diterpenes are produced that can raise artery-damaging LDL cholesterol. However, these chemicals are almost absent from filtered and instant coffee. Knowing I have a cholesterol problem, I dissected a coffee pod and found a paper filter lining the plastic cup—whew!

Popular additions that some people use, such as cream and sweet syrups, also counteract coffee’s potential health benefits by turning the calorie-free beverage into a high-calorie dessert. “All the things people put in coffee can result in junk food with up to 500 or 600 calories,” Willett said. For example, a Starbucks Mocha Frappuccino has 51 grams of sugar, 15 grams of fat (10 of which are saturated), and 370 calories.

With cold brew season just around the corner, more people are likely to turn to cold brew coffee. Currently on the rise in popularity, cold brew coffee counteracts the natural acidity of coffee and the bitter taste that comes from pouring boiling water over the beans. Cold brew coffee is made by steeping the beans in cold water for several hours, then filtering the liquid through a paper filter to remove the harmful grits and diterpenes while retaining the flavor and caffeine you enjoy. Cold brew coffee can also be made with decaffeinated coffee.

Decaffeinated coffee is not entirely devoid of health benefits. As with caffeinated coffee, the polyphenols it contains have anti-inflammatory properties that may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes and cancer.

+ There are no comments

Add yours